Textile Circularity — A Decade of Experiments and Experiences at Meemansa

- Manish Kothari - rhinomk

- Oct 20, 2025

- 7 min read

Introduction

The textile industry is a paradox: it is a generator of beauty, culture, and livelihoods — yet also one of the most resource-intensive and waste-producing sectors in the world. India, with its deep textile traditions and massive industrial base, sits at the heart of this paradox.

Circularity in textiles is not only about recycling garments at end-of-life. It is about re-imagining the fabric value chain from its very beginning: how fibres are sourced, how fabrics are designed and cut, how garments are made and distributed, and ultimately, how they are used, reused, and disposed.

At Meemansa, for over a decade, we have worked to embed upcycling, zero waste, and inclusivity into this value chain. Partnering with Rhino Machines, we have combined design ingenuity, engineering capabilities, and community partnerships to explore how waste can be transformed into value.

Types of Fabrics in the Waste Stream

Different fibres behave differently in their lifecycle, making the recycling of textiles particularly complex compared to other waste streams like plastics. The fabrics in today’s textile waste can be broadly classified as:

Category | Fabrics | Notes |

Biodegradable | Cotton, Linen, Hemp, Jute, Wool, Silk | Natural fibres that decompose under natural conditions. High potential for recycling into yarn or composting. |

Semi-degradable | Blends (Cotton-Polyester, Poly-cotton, Wool-Synthetic, Viscose, Modal, Rayon) | These combine natural and synthetic fibres. They only partially degrade, and separating components is technologically challenging. |

Non-biodegradable | Polyester, Nylon, Acrylic, Spandex, Other synthetics | Petrochemical-based fibres that do not decompose naturally. Their recycling infrastructure in India is minimal, making them landfill-heavy. |

This diversity shows why textile recycling is considered harder than plastics recycling. With blends dominating fast fashion, solutions must span from waste prevention (upstream design) to technological regeneration (fibre-to-fibre recycling).

Sources of Textile Waste

Waste is generated throughout the textile lifecycle:

Pre-production (Upstream): Inefficient cutting plans, misaligned fabric widths, or design choices that create high offcut percentages.

Production (Mid-stream): Side-cuts, rejected fabric rolls, trims, overstock, or misprints. This is perhaps the largest source of industrial waste.

Post-use (Downstream): Consumer discards, returned goods, and garments at end-of-life, packaging. Blended, dyed, and mixed materials make this the hardest to recycle.

Recognising these streams is critical. Without clarity on where waste arises, interventions cannot be designed.

This has been the starting point of Meemansa’s journey.

The Fabric Value Chain: From Source to Post-Use

The textile industry operates like a vast river: (perhaps about 56 hands change when making one garment)

Fibre sourcing — natural or synthetic, each comes with its ecological cost. Cotton consumes water and pesticides, while synthetics are petroleum-derived.

Fabric production — dyeing, finishing, and weaving add chemical, thermal, and water footprints.

Garment manufacturing — design inefficiencies and cutting losses create piles of offcuts.

Distribution and retail — unsold stock or fast-changing trends create dead inventory.

Consumer stage — garments are discarded at an alarming pace, with very little structured collection.

Each stage represents a point of leakage of value and creation of waste. To build circularity, one must address every stage, not just post-consumer waste.

The Challenges of Textile Waste

Across the chain, three major challenges dominate:

Pre-Production inefficiencies — Wastage begins at the design table when fabric widths do not match patterns, or when cutting plans are careless.

Production waste — Offcuts and rejects pile up, often burned, dumped, or sold as rags.

Post Use chaos — Post-use garments are mixed, blended, and unsegregated, packing bags are dumped and mixed up, making recycling nearly impossible, ending the life of textile before its time.

Textile waste is often semi-visible. Unlike municipal waste, it is not piled on the streets — it sits in factory corners, warehouse godowns, or inside households, hidden from public view. This invisibility makes action slower.

Meemansa’s Interventions Across the Value Chain

Pre-Production: Mindful Fabric Utilisation

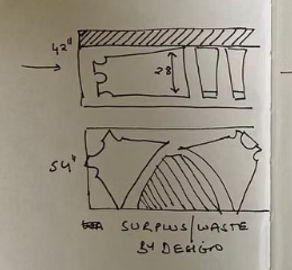

Circularity starts at the drawing board. At Meemansa, designers consciously:

Align product design with fabric widths.

Optimise cutting plans to minimise offcuts.

Use creative pattern engineering to prevent wastage.

One sketch by Priyanka Bapna illustrated how a thoughtful cutting plan reduced wastage by double digits. This is where circularity begins: not in recycling, but in waste prevention through design thinking.

Meticuluous planning of cutting, by designers, using digital software by Meemansa has been a practice to optimize the pre-production use efficiency of fabric

Post Production:

Upcycling Production Waste with NGO - Social Ecosystem

1. Animedh Charitable Trust (ACT, Mumbai)

One of Meemansa’s earliest pilots.

Side-cuts from fabric production were turned into jholas (cloth bags).

Women from underprivileged families in Goregaon were trained and supported.

This provided the first insights into how upcycling can merge waste and livelihood creation, seeding later initiatives.

2. iPartner (Tonk, Rajasthan)

Under the Upcycled Revolution, Meemansa partnered with iPartner India and Cecoedecon to establish Apno Rakshan Kendra.

Women in Tonk stitched “Jholas of Love” from waste fabrics.

A repurchase model ensured they earned from day one.

The project scaled with more centres, empowering women with income and dignity.

3. Meemansa Anand (Gujarat)

In 2019, Meemansa set up its first in-house production base in Anand.

Local women were trained alongside skilled karigars.

Starting with jholas, they graduated to kurtis and eventually mainstream garments.

Today:

10 full-time women stitch daily.

5 manage layering, cutting, and finishing.

Dozens stitch jholas from home.

This proved upcycling is not only waste utilisation but a ladder for continuous skill building and stable livelihoods.

4. Corporate Textile Conglomerate Collaboration

Meemansa reimagined the Congolomoreate's fabric surplus.

Turned into bags, accessories, and corporate gifting products.

Demonstrated how corporate partnerships can embed circularity.

5. Head Held High (Antarprerana Project), an extension of GAP collaboration

A community-led stitching ecosystem across multiple regions in Karnataka, Maharashtra

At Wadi pre-covid provided physical and virtual training to tailors and support staff produce jholas, pouches, yoga bags, cushion covers.

Capacity: 13,600 bags/month was established.

Empowered rural women to become income earners and future entrepreneurs.

6. COVID Mask Innovation (Meemansa + IIT Bombay + Rhino Machines)

During the pandemic, single-use synthetic masks created a new waste stream.

Meemansa partnered with IIT Bombay to use Duraprot coating on cotton masks, giving them antiviral protection equivalent to surgical/N95.

Masks could be reused for 60–100 days, reducing disposal volumes.

Rhino Machines engineered mechanised solutions for coating and scaling production, turning innovation into a replicable process.

A landmark example of integrated value chains: Research (IITB) + Design (Meemansa) + Engineering (Rhino).

Post Use : Repurposing with Innvoative solutions

1. Large exporter of Polyster Fabric

Diverted post-use polyster textile discards into new products.

Worked with artisans / women in and around Meemansa Mumbai

Proved industrial circularity is possible at scale.

2. Jai Vakeel Foundation

Together with Meemansa, regenerated production and post production waste into new woven fabrics.

Engaged intellectually challenged individuals in production.

A powerful model of inclusivity and technology convergence.

3. Masala Company

Concerned about their used gunny bags, The Masala company sought solutions.

Meemansa converted them into canopies, bags, and bottle covers.

Products looped back for their own use and gifting.

4. E4F Resurrect

Meemansa partnered to process collected consumer waste into jholas.

Products were reintroduced into daily circulation.

5. Haiko Supermarket

Among the first stores to replace checkout bags with upcycled jholas from Meemansa.

Made sustainability visible to everyday consumers.

Ecosystem and Technology: Support from Rhino Machines

Meemansa’s model was strengthened by Rhino Machines, which brought:

Engineering scale-up of pilots into replicable systems.

Cross-learning from sand reclamation and Silica Plastic Block projects.

A culture of PPP-style partnerships, linking industries, NGOs, SHGs, and consumers.

The mindset of technology as an enabler of circularity.

Social & Cultural Dimensions

Women empowerment: Over 500+ women engaged in stitching, cutting, finishing, and home-based work.

Livelihood creation: Micro-factories and distributed production models created sustainable income sources.

Inclusivity: Equal opportunities extended to intellectually challenged individuals.

Cultural narrative: Every upcycled product carries a story of transformation — from waste to dignity.

Outcomes, Learnings, and Challenges

Outcomes

From its decade-long journey, Meemansa demonstrated:

Waste prevented through upstream design.

Waste transformed into valuable products midstream.

Waste repurposed into functional goods downstream.

Systems built for replication — through MOU models, NGO partnerships, and the Anand in-house facility.

Alignment with SDGs:

SDG 5 (Gender Equality)

SDG 8 (Decent Work)

SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure)

SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production)

SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals)

Challenges & Learnings

At the same time, sustaining these models surfaced systemic challenges — along with pathways forward:

Fragile Value Chains

Waste-to-value chains collapse easily when profit-only thinking dominates.

Learning/Solution: HiEERA’s 3P model (People, Planet, Profit) integrates diverse stakeholders into one resilient system.

Scientists and Innovators Outside the Chain

Textile blends and mixed waste streams are technologically harder than plastics, yet researchers are disconnected.

Learning/Solution: Integrating scientists and technologists into the chain as co-creators to drive fibre regeneration solutions.

Market Acceptance and Pricing

Upcycled products face resistance in price-driven markets dominated by fresh-fabric goods.

Learning/Solution: EPR (Extended Producer Responsibility) for textiles could offset costs and normalise upcycled procurement.

Lack of Organised Local Systems

Collection, segregation, and market linkages are weak, raising handling costs.

Learning/Solution: Develop Integrated Solid Waste Management (ISWM) adapted to textiles, combining centralised and decentralised models.

Absence of Digital Traceability

Fabric movement and waste flows are not digitally tracked.

Learning/Solution: Use mobile applications linked to manufacturer databases and GST fabric movement records for traceability by design. This would generate data to plan interventions and reduce fragmentation.

Looking Ahead

Meemansa recognises that textile circularity cannot be scaled in silos. The future lies in building multi-stakeholder systems.

The founders have subscribed to the Empretec India Foundation’s HiEERA program (High Impact Entrepreneurs for Emerging Regions for Action). The vision is to develop a HiEERA Complex model — collapsing the entire textile value chain into one integrated enterprise, where supply and demand sit side by side.

By being part of stitching together Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) under HiEERA’s diverse thinkers, Meemansa aims to move textile circularity from scattered pilots to mainstream practice, rooted in accountability, culture, and the 3P bottom line.

Conclusion

Textile circularity is not a distant dream — it is a craft practiced daily. Meemansa’s decade-long experiments show that waste can indeed be transformed into value when design, technology, and community converge.

With Rhino Machines as an engineering partner, Meemansa continues to weave a culture of excellence, circularity, and social impact, proving that sustainability and livelihoods can go hand in hand.

Participating in the Empretec HiEERA program provides yet another step forward — offering a way to stitch together the fragmented circularity value chain into a sustainable ecosystem. Unlike traditional supply chains driven solely by profit, this ecosystem is designed to adapt and evolve with time, governed by community-conscious thinkers who balance People, Planet, and Profit.

This, perhaps, is the true promise of textile circularity: not just recycling fabric, but reweaving value chains, cultures, and communities into a resilient future.

Comments